The Arctic Destabilization Lab

Why We Go North – Georgetown in the Arctic

Professor Jeremy T. Mathis

April 11, 2023

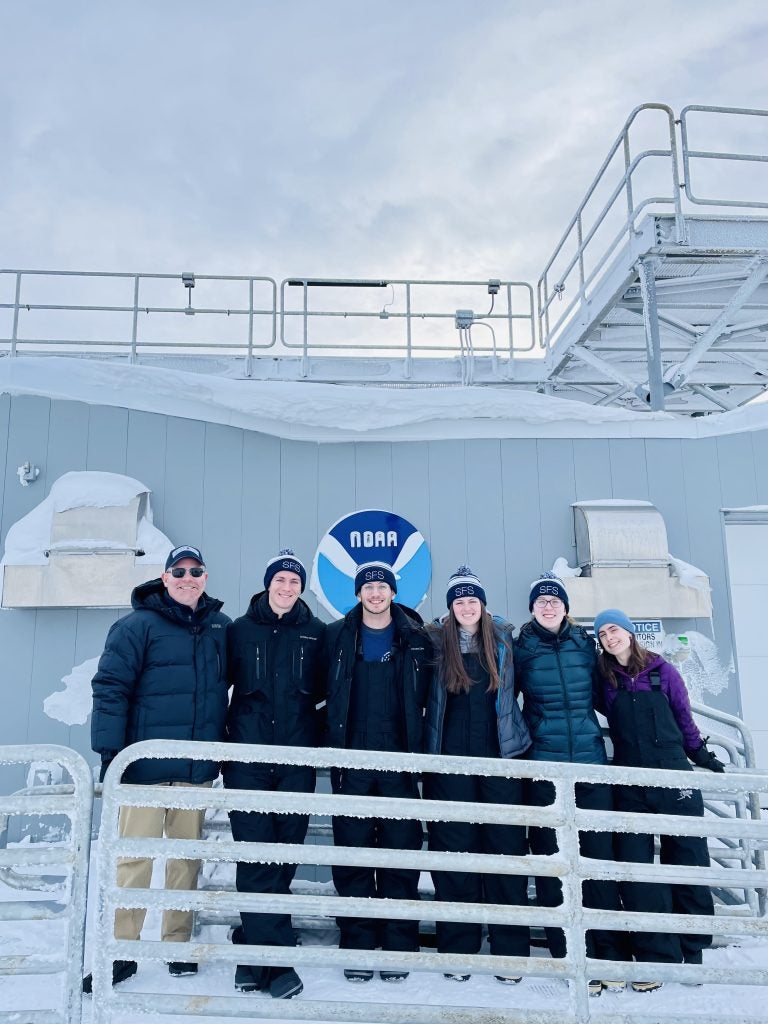

On the 20th Anniversary of my first trip to the Arctic, I landed in Utqiagvik, Alaska, the northernmost city in the United States, on a grey afternoon with ten Georgetown University undergraduate students. They were spending their spring breaks trying to understand the unique challenges the region faces as it buckles under the most rapid and abrupt climate change on Earth.

The tiny airport was bursting at the seams as we gathered our bags amongst the tote bins full of food and other necessities that local residents had packed in Anchorage. More than 4,000 people live in Utqiagvik, which is 320 miles north of the Arctic Circle. The predominantly Inupiat community has survived there for more than 1,500 years largely by hunting whales, seals, and walrus from the sea ice that used to stretch from their backyards all the way to the North Pole. But those days are gone.

Since 2003, the Arctic has lost an unprecedented amount of sea ice as temperatures have risen more than three times faster than the rest of the planet because of a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. As white surfaces formerly covered in sea ice and snowpack give way to blue ocean and greening tundra, the Arctic is now absorbing vast quantities of heat from the sun rather than reflecting it back into space. The implications of this reality for the region and the entire planet are profound.

Because Utqiagvik lies at the frontier of human civilization, it’s always been a difficult place to visit. But over the years, I’ve seen alarming changes to the tight-knit community that has relied on fortitude and adaptability to survive in a harsh environment. Unfortunately, extreme climate disruptions may finally break the ties that have kept the Inupiat on this land for centuries, and I wanted my Georgetown students to see what was happening for themselves.

The disappearing sea ice is making it more difficult for the community to harvest bowhead whales and seals that have fed them since prehistoric times. The cultural identity and family structure of Alaska Native villages like Utqiagvik are built around their subsistence hunting practices and if those traditions are broken, everything else goes with them. Families are left with food insecurity as the cost of groceries at the one store in town are exorbitant and out of reach for most residents. As hunting becomes more difficult, the loss of purpose has left an entire generation of young men in the community adrift, leading to an epidemic of drug and alcohol abuse, domestic violence, abandoned children, and suicide. And there are many other challenges.

Energy costs in villages like Utqiagvik are four to ten times higher than the national average. Educational opportunities are limited, and even basic healthcare requires a costly trip to Anchorage, especially for mental health. Stronger storms, sea level rise, and erosion are pummeling the coast and wrecking infrastructure. Every aspect of the community is at risk.

On our first morning in Utqiagvik, I walked the students out onto what was left of the sea ice, being careful to avoid the polar bear that had been lurking around the night before and trying not to fall through the thin ice. I first walked out on the sea ice in 2003, and it was upwards of 10 feet thick. Now, the few inches of sea ice that separated us from the rapidly warming ocean beneath our feet was just a remnant of what it once was, and in the next two decades, summer sea ice will likely disappear completely from the Arctic Ocean if we don’t slow planetary warming.

It struck me that when these students come to Utqiagvik on their 20th Anniversary, the sea ice may be gone and perhaps much of Utqiagvik with it. But neither of those outcomes are guaranteed if proactive policies can be implemented at local, state, national, and international levels to protect the environment and the people who rely on it. But policymakers must step up now and make hard choices.

As we spent the morning exploring the ice off Utqiagvik, I experienced many emotions. I was sad because I know the hardships communities will face as climate change continues to ravage the environment and a way of life that has persisted for generations. However, I was also grateful that Georgetown provided the students the opportunity to go to a place where they could truly see the impacts of what a changing climate will bring. Mostly though, I was incredibly hopeful, knowing that these ten students are going to bring their talents, insights, and compassion to solve the problems we face collectively as a nation and as a world.

Olivia Geist, a junior in the School of Foreign Service (SFS) majoring in Culture and Politics and focusing on Gender and Sustainability told me, “I think I have a better understanding of the disconnect between policy and lived experience, especially since I study domestic violence issues that are very sensitive subjects in small communities. I was surprised by how much distrust could be bridged by a sincere, unplanned conversation; taking time to listen and build relationships where you can is far more valuable than going where you are not invited.”

Catie Malone, a senior in the SFS majoring in Science, Technology, and International Affairs said, “In Utqiagvik, it became clear to me that the value of our stay was in our ability to raise awareness for climate change and the ways indigenous communities will be affected. In doing so, we can hope to encourage more informed responses to the climate crisis, its consequences, and other issues arising in the Arctic. We may not have every solution and we certainly cannot speak for indigenous populations, but their realities and experiences must be a greater part of political discussions.”

People ask me why I keep going north to the Arctic after all these years. My answer is simple. So I can show a new generation of problem solvers the realities of a rapidly changing world. Not to scare them, but to empower them. Because as long as we have students who are willing to take on these challenges, I have every confidence we will find our way forward. And if policymakers today can’t figure out what to do about the Arctic, then I know ten Georgetown students who are ready to take their places.